The Evolution of ALM Applications

ALM (Agile Lifecycle Management) solutions, i.e. applications that help Agile teams deliver software solutions, have come a long way. They started out as tools to manage a backlog and assist teams with working on stories and defects in sprints. Then came collaboration features, reporting and the ability to work in Kanban. As the number of teams grew and more complicated work had to be organized and managed, portfolio items/epics appeared which helped group related stories into higher level aggregates.

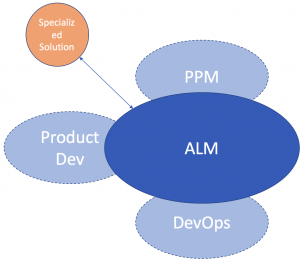

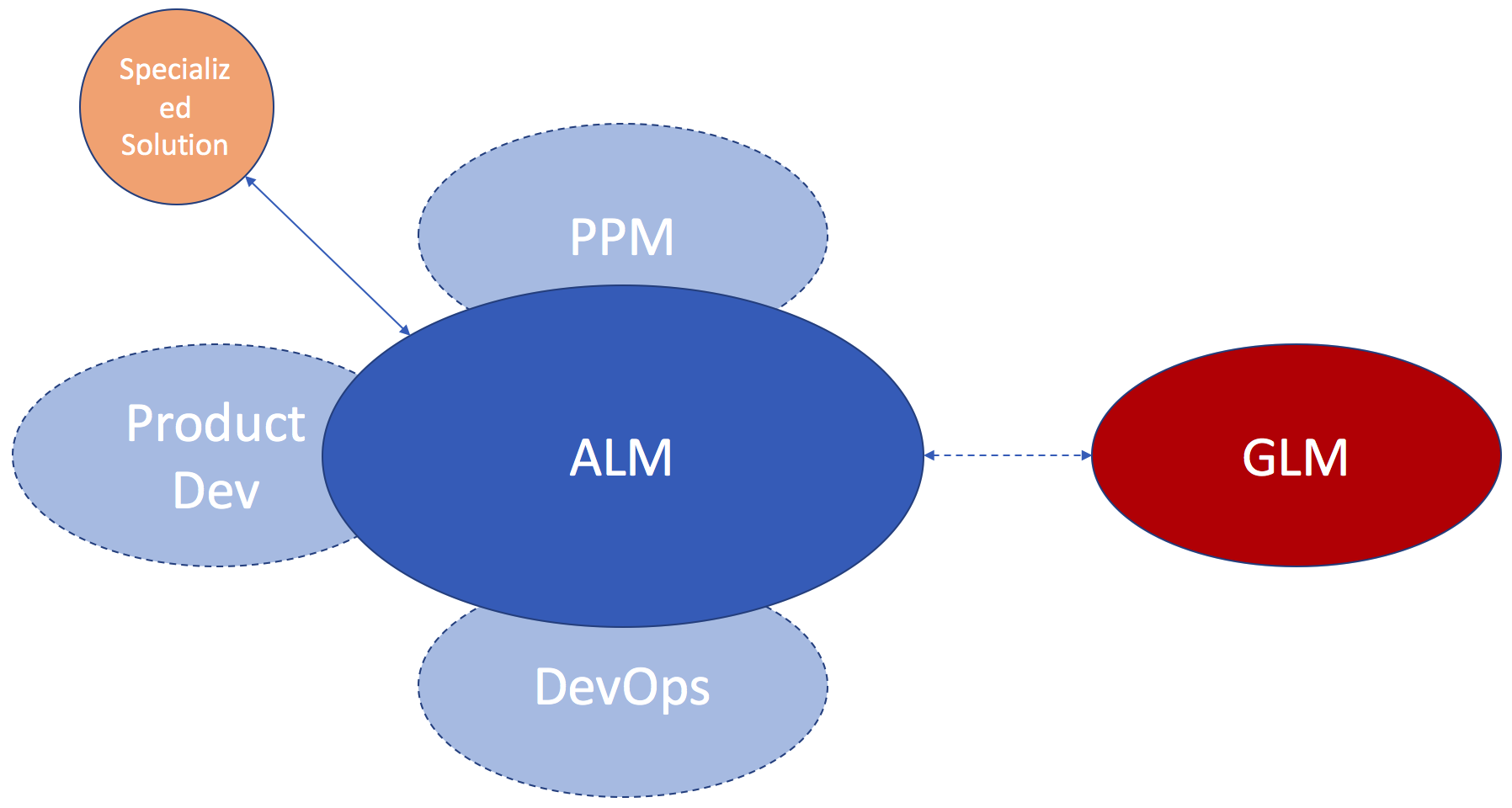

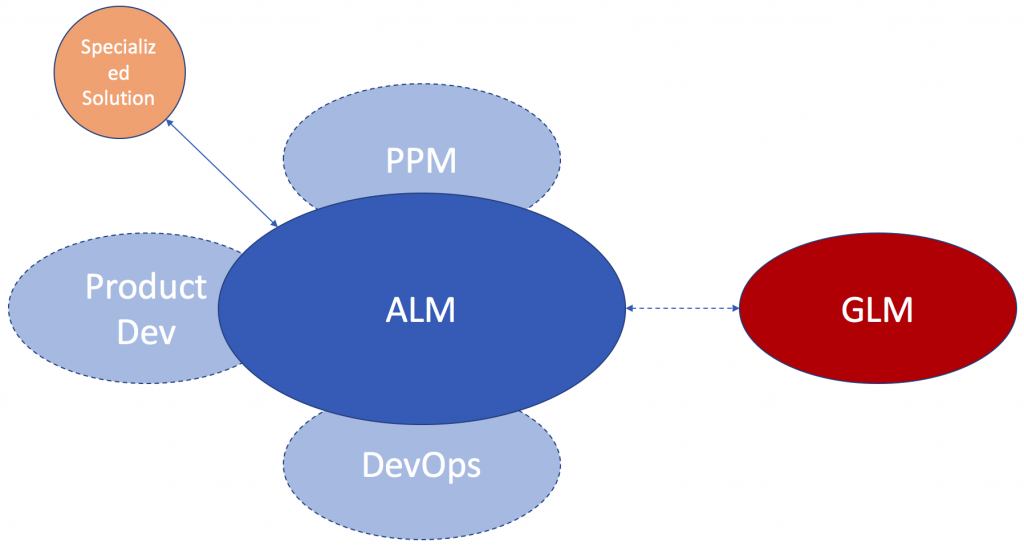

In recent years, the ALMs (such as VersionOne) increased their functional footprint into other adjacent areas:

- PPM – project portfolio management: Higher level roll-ups, reporting, forecasting and even budget tracking were introduced in the attempt to meet the needs of leaders and manage portfolios of work..

- Product planning and roadmapping – This area, which is still in the early stages of being conquered by ALMs, involves product strategy, ideation & planning, roadmapping, story mapping, etc., i.e. The part of the product life cycle before items are defined enough to be worked by Agile teams.

- DevOps – The realization that fully tested software coming out of Agile teams by itself adds no value until it is deployed and running in production was catalyst for forays into DevOps and automation to accelerate and automate the “last mile” of the development process with the goal of increased visibility and ultimately continuous deployment.

While the ALMs aim to cover core functionality in these different areas and continue to push their boundaries, it is also common to offer integrations for more sophisticated solutions in these areas in case the ALM customers demand highly specialized functionality.

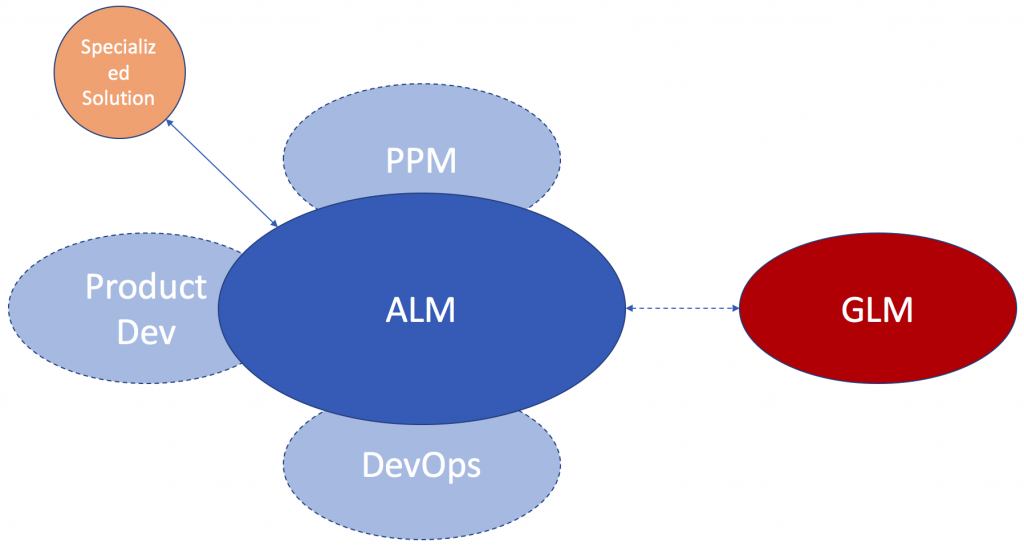

The Next Frontier: GLM

While ALMs do a good job of ushering work items through the Agile process and even carry it all the way to becoming deployed software in production, there is a different class of items that – often invisibly – work their way through Agile teams and organizations: growth and learning. As Agilists we know that our teams, programs and portfolios should constantly evolve and improve. We are inspecting and adapting and applying Kaizen on an ongoing basis to improve.

The “items” in this case are not stories, defects or even epics/portfolio items; they are improvements and learning objectives (I’ll refer to these as growth items). At the team level, growth items may result from retrospective meetings and sometimes manifest themselves as improvement stories (or issues) in the ALM’s sprint backlogs or on the wall in the team room. While growth items are fundamentally different than stories and defects, making them visible as part of the backlog ensures the team remains focused on dealing with them.

This approach at the team level works reasonably well, although growth items are a different class of items and often don’t follow the same rules and flow of regular backlog items. Example: these improvements are often not part of the sprint commitment because they may require more time to resolve. Including them as part of tasking and burn down may also not work overly well. Frequently, growth items also require experimentation and several rounds of inspection and adaption spanning multiple sprints before they can be considered resolved.

Today’s ALMs may offer some solutions for team-level growth items but often that functionality is more of an afterthought. Where the approach breaks down even more is when those growth items that are outside the teams’ control and need attention and resolution by higher level entities, which could be programs, portfolios, functional leaders and senior management (example: a company’s facilities do not provide sufficient space for teams to collocate and effective collaborate). (See also: Closing the Impediment Gap.)

The ALMs don’t currently provide functionality to effectively deal with organizational growth items and I would argue that similar to specialized solutions for other adjacent areas there is room here for a new class of solutions I’d like to call Growth Lifecycle Management (GLM) applications. With learning and improvements being at the core of healthy Agile/Lean enterprises, GLMs should provide the mechanisms to capture, communicate, aggregate, analyze growth items, manage their resolution and analyze their impact on an organization. The latter will ultimately require integration and sharing of data with traditional ALMs in order to facilitate the correlation of growth item resolution and team and organizational performance.

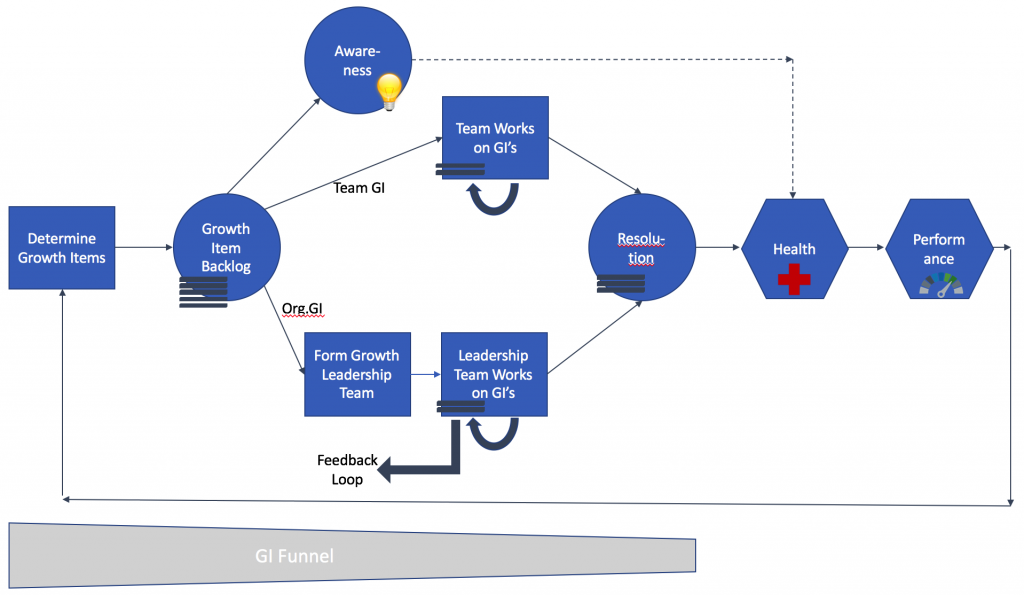

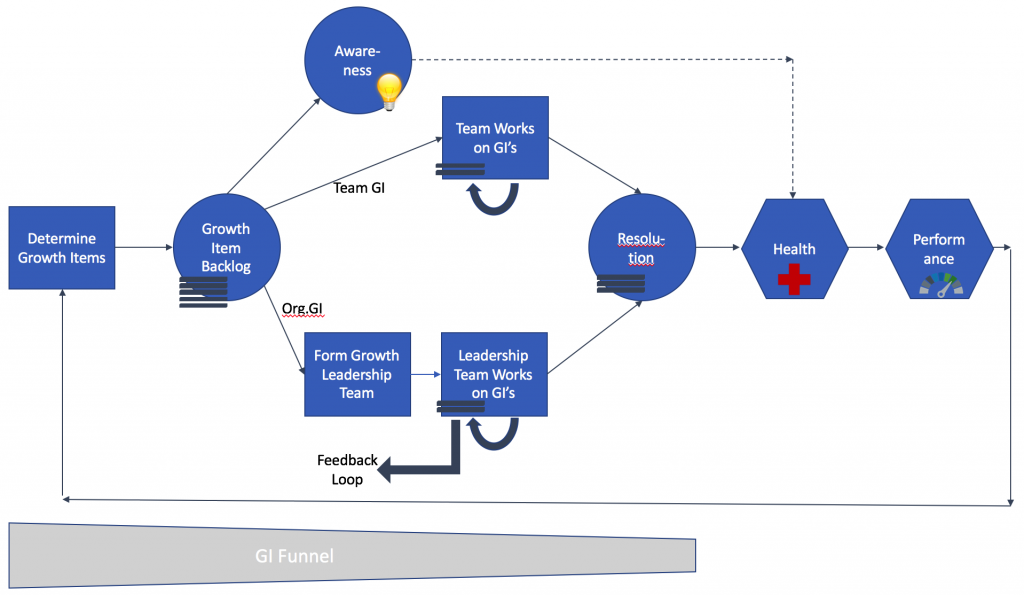

The Growth Item Value Loop

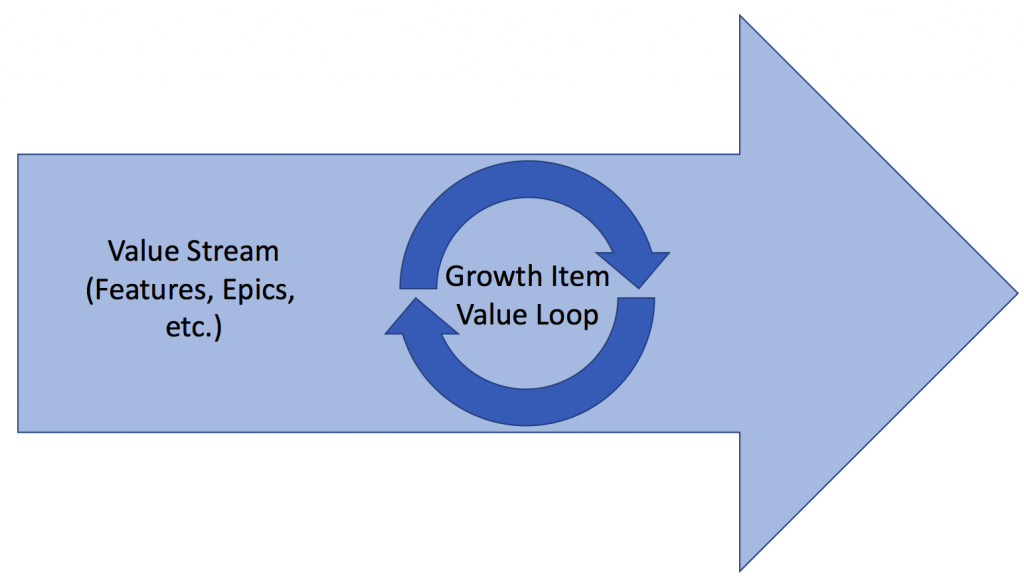

In the Agile world, many of us are familiar with the concept of value stream: items of value (stories, features, etc.) flow through a series of steps after which value is delivered to the organization, e.g. by users being able to utilize new functionality in production. The flow in this case is unidirectional (often depicted left to right) and in most cases all items make it through the stream beginning to end.

Growth items tend to behave differently: First of all, not all items make it through the various steps. More like a sales funnel, at each step items may be dropped or dismissed, which reduces to potential output of value and limits the number of items exiting the process compared to the number of items entering the process. Examples: teams end up not implementing improvements they identified or leaders only select 4 out 10 identified organizational growth items based on capacity or expected ROI.

Secondly, the process isn’t strictly unidirectional with a single entry and exit point. Growth and incremental improvements are based on feedback loops. At the team level, members experiment with things that may resolve impediments and inspect & adapt. At the leadership level, leaders resolving organization growth item provide feedback to the teams which positively affects the health and motivates the teams and creates a self-reinforcing loop.

Due to these differences compared to the commonly used concept of value stream, I propose the term “value loop”. Let’s look at the steps in detail:

- Growth items get identified through Agile ceremonies such as sprint retrospectives or strategic retrospectives as suggested by AgilityHealth.

- Growth items get collected in a growth backlog and prioritized.

- Items that teams have the ability to address get worked on by Agile teams. Due to teams’ limited capacity only the highest value items may get worked on. Experimentation and inspect & adapt results in feedback loops and iteration over time.

- Organizational growth items that teams themselves cannot resolve themselves require leadership to get involved. Leadership teams have to be formed consisting of at those leaders that have a stake in and ability to resolve those items.

- Once formed, growth leadership teams work on addressing the highest value items since these teams too are often constraint in their capacity. When they are able to resolve items, feedback should be provided to the teams that identified the growth items, so that teams see that their voices are heard and that leadership takes them seriously and is interested in enabling them go get better and healthier. This type of feedback will reinforce the value of this process.

- Out of all items on the growth backlog, the most pressing items will hopefully see resolution by teams and leadership.

- The immediate impact of resolved growth items is improved team health, which has various components including morale/happiness, effectiveness, level of collaboration, and skills.

- Improved team health will result in improved team performance which manifests itself in higher quality, throughput, value delivered or customer satisfaction which should tangibly benefit the organization and its financial performance.

I used the term “value loop” since the overall process is iterative and continuous as opposed to linear in nature. Improvements never stop and feed on each other as also suggested by “Kaizen”.

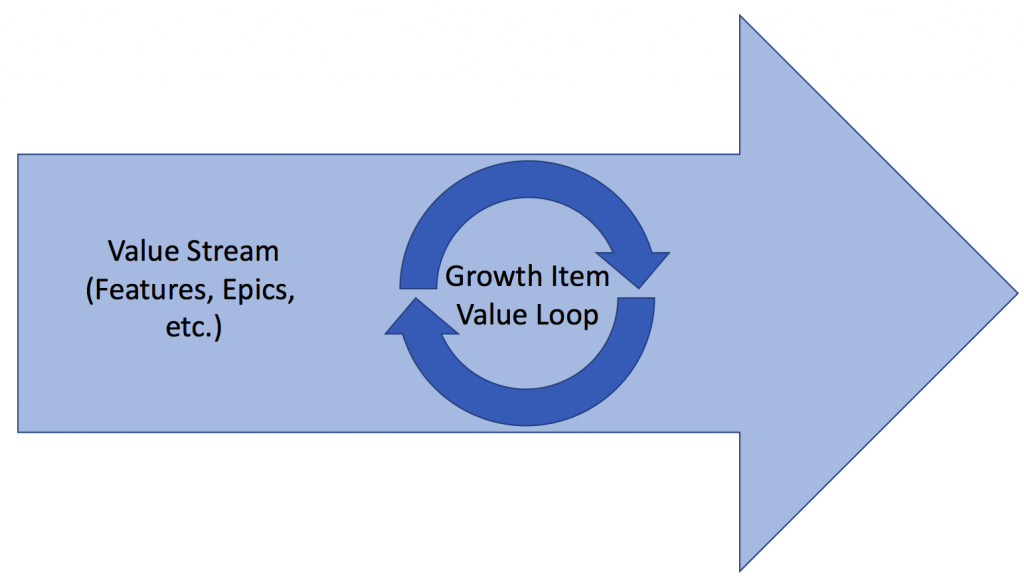

What’s the relationship between the Growth Item Value Loop and the regular value streams? The Growth Item Value Loop lives inside the value stream. As it spins and picks up speed, it can act as an accelerator to the overall value stream as the improvements in health and performance positively affects the overall value stream performance. This dynamic also makes a compelling business case for focusing energy on the Growth Item Value Loop.

In Summary: The growth item lifecycle is very different than the lifecycle of traditional work items going through their value stream. Despite various vectors of functional growth, current ALM solutions do not effectively encapsulate the Growth Item Value Loop. Since this loop is at the core of Lean/Agile and valuable accelerant with tangible business impacts, there is room for application providers to cover this still relatively uncharted territory of GLM.

In the context of Lean Product Development, there are now a number of acronyms in circulation among Product Managers and Agilists and many of them are similar and seem to overlap. In essence, they are all rooted in the belief that it doesn’t make sense to launch and release complete, feature-rich products which take many months (or even years!) to develop without first obtaining market feedback to validate that one has a good understanding of the problem to be solved and a viable solution for it.

In the context of Lean Product Development, there are now a number of acronyms in circulation among Product Managers and Agilists and many of them are similar and seem to overlap. In essence, they are all rooted in the belief that it doesn’t make sense to launch and release complete, feature-rich products which take many months (or even years!) to develop without first obtaining market feedback to validate that one has a good understanding of the problem to be solved and a viable solution for it.

When people take a mechanistic view of an organization, they believe it can successfully and exhaustively be described through its structure and processes. There are clear inputs and outputs that can and should be measured (and shown on dashboards). Clear correlations and relationships exist and metrics are driven through use of known “levers”. Order is created by following consistent processes and best practices. The people that make up these organizations are “resources” and certainly play an important role, but at end of the day it’s about hiring, training, retaining and measuring engagement. This world has clear rules and could be described by a good deterministic model with underlying predictable formulas and mechanisms. At its foundation, this view of organizations is rooted in

When people take a mechanistic view of an organization, they believe it can successfully and exhaustively be described through its structure and processes. There are clear inputs and outputs that can and should be measured (and shown on dashboards). Clear correlations and relationships exist and metrics are driven through use of known “levers”. Order is created by following consistent processes and best practices. The people that make up these organizations are “resources” and certainly play an important role, but at end of the day it’s about hiring, training, retaining and measuring engagement. This world has clear rules and could be described by a good deterministic model with underlying predictable formulas and mechanisms. At its foundation, this view of organizations is rooted in  On the other side of the spectrum, we find individuals thinking of an organization in humanistic terms. Organizations are organic and the sum of the individuals and teams they are made up of. These “cells” form an organism that often doesn’t follow predictable rules but functions through complex interactions and relationships that often escape the attempt of description via simple mathematical models. While org charts and processes do exist, the humanistic view accepts that these are solely simplistic attempts at describing how such an organization really works. This thinking is more in line with the theory of

On the other side of the spectrum, we find individuals thinking of an organization in humanistic terms. Organizations are organic and the sum of the individuals and teams they are made up of. These “cells” form an organism that often doesn’t follow predictable rules but functions through complex interactions and relationships that often escape the attempt of description via simple mathematical models. While org charts and processes do exist, the humanistic view accepts that these are solely simplistic attempts at describing how such an organization really works. This thinking is more in line with the theory of

Back to Agile: is there something equivalent to technical debt when it comes to transforming teams and an organization and moving them to Agile? I would argue yes, there is. Let’s think about some examples.

Back to Agile: is there something equivalent to technical debt when it comes to transforming teams and an organization and moving them to Agile? I would argue yes, there is. Let’s think about some examples.

Organizational agility: enabling the organization to act and react quickly to environmental and market conditions.

Organizational agility: enabling the organization to act and react quickly to environmental and market conditions.

immediate attention and action, such as leading a transformation or increasing the maturity of a group of teams. The person comes in with with an objective and expectation of results, which may translate into some kind of mandate and organizational power and influence. It’s like building a house where quickly a foundation is laid upon which parts are assembled to produce a building, the desired outcome of an engagement. Ideally the building isn’t hacked together over a few days, but there is certainly the desire to complete the building upon a solid foundation over several weeks or months. Then the person moves on to the next building or leaves the organization with the goal accomplished.

immediate attention and action, such as leading a transformation or increasing the maturity of a group of teams. The person comes in with with an objective and expectation of results, which may translate into some kind of mandate and organizational power and influence. It’s like building a house where quickly a foundation is laid upon which parts are assembled to produce a building, the desired outcome of an engagement. Ideally the building isn’t hacked together over a few days, but there is certainly the desire to complete the building upon a solid foundation over several weeks or months. Then the person moves on to the next building or leaves the organization with the goal accomplished. nd getting people to see the value in coaching, so that that they will want to consume this service. A new person entering a company in this role will find himself in more of a “planting” mode where he’ll put various seeds in the ground in several locations and continue to water. This process will take time and patience and only few plants will spring out of the ground quickly. In most cases it may take months for the majority of plants to take root and then emerge from the soil. There are no guarantees and shortcuts to accelerate the process. Despite best efforts, not all seeds will come to life. With the coach building solid relationships, trust and “pull”, ultimately large plants with deep roots will flourish over time. These plants are a natural extension of the environment and will hopefully be able to weather storms and persist long-term. This is different from erected buildings, which are typically more like foreign objects in nature, with more shallow foundations, which may make them more susceptible to natural forces.

nd getting people to see the value in coaching, so that that they will want to consume this service. A new person entering a company in this role will find himself in more of a “planting” mode where he’ll put various seeds in the ground in several locations and continue to water. This process will take time and patience and only few plants will spring out of the ground quickly. In most cases it may take months for the majority of plants to take root and then emerge from the soil. There are no guarantees and shortcuts to accelerate the process. Despite best efforts, not all seeds will come to life. With the coach building solid relationships, trust and “pull”, ultimately large plants with deep roots will flourish over time. These plants are a natural extension of the environment and will hopefully be able to weather storms and persist long-term. This is different from erected buildings, which are typically more like foreign objects in nature, with more shallow foundations, which may make them more susceptible to natural forces. I recently went through the SAFe SPC4 class, which was quite interesting in the light of my earlier post about “

I recently went through the SAFe SPC4 class, which was quite interesting in the light of my earlier post about “